Fundamental Fire

When they were carved in the second century CE, the two colossal Buddhas of Bamiyan gazed out from the sandstone cliffs at a thriving Buddhist civilisation that stretched North from Pakistan and along the Silk Road to Western China. At 174ft, the tallest Buddha was until this year the largest standing Buddha image in existence and one of the world’s largest statues; the cliffs around them still contained tunnels and painted caves that were the remains of a vast ancient Buddhist monastery. In the ninth century CE Arab invaders ruined the Buddhas’ plaster faces; 400 years later Ghengis Khan battered them with rocks. But they faced their greatest danger after 1997 when fighters of the fundamentalist Taliban movement captured the area. A Taliban commander blew up the head of the smaller Buddha, fired rockets at the groin and dress of the larger Buddha and then dumped two burning tyres on its lip.

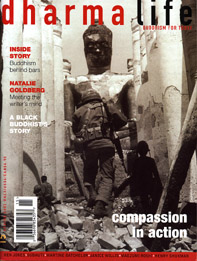

Perhaps in response to worldwide protests Mullah Mohammed Omar, supreme leader of the Taliban, who rule 95 per cent of Afghanistan, called a halt to the attacks, promising to protect the country’s heritage. But in February Omar ordered the destruction of all pre-Islamic statues. His edict declared, ‘Because God is one God and these statues are there to be worshipped and that is wrong, they should be destroyed so that they are not worshipped now or in the future’. He ordered the Ministry of Vice and Virtue to send its men out to destroy all statues in Afghanistan. In early March the threat was carried out. Despite the last-minute efforts of UN Secretary General, Kofi Anan, dynamite was planted in holes drilled in the Buddhas and layer after layer of rock was blown away, until the Buddhas had vanished.

The Bamiyan Buddhas are only the best known relics that are threatened by the edict. Around the country, at many archaeological sites and in Kabul’s National museum, there are thousands of relics of one of the greatest Buddhist civilisations, some of outstanding beauty or historical importance.

The destruction was greeted by an international outcry. UNESCO, who had designated Bamiyan a World Heritage Site demanded that the Taliban ‘halt the destruction of (Afghanistan’s) cultural heritage’. India called it ‘an outrage’, and offered to take responsibility for Bamiyan. But Omar dismissed objections. ‘According to Islam, I don’t worry about anything. My job is the implementation of Islamic order. Islamic law is the only law acceptable to me.’ The Taliban government is only recognised by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Their commitment to Islam has been reinforced by international isolation and decades of war. As one specialist in Afghan archaeology told Dharma Life, ‘the archaeological damage is horrific, but everything that has happened in Afghanistan in the past 20 years has been horrific’. In that time the country has experienced almost ceaseless wars in which 1.5 million people have died.

The roots of the assault on Afghanistan’s Buddhist heritage lie deep in history. Islam inherited a horror of idolatry and a mistrust of images from the Bible’s Second Commandment not to make graven images. The Koran is ambiguous in its stance on images, but Mohammed himself smashed idols, and Islamic law has usually forbidden the making of images. The Taliban follow a very strict interpretation of Sunni Islam. They ban most forms of light entertainment, all photography, and the depiction of the human face. Religious images are considered particularly abhorrent, because it is thought that the image itself is worshipped rather than what it signifies.

Afghanistan has a long history of iconoclasm, but it is possible, however, that a more narrowly political motivation lay behind the destruction. UN-imposed economic sanctions, comingafter decades of war havedevastated Afghanistan’s economy, and the country faces a famine, which threatens 1.5 million lives. Commentators speculated that the threat to the country’s heritage might be a bargaining chip. However the Taliban have shown no interest in discussing their policy with outsiders, and it may also be that, given the extent of their international isolation, they have nothing to lose.

The National Museum has been the focus of intrigue for a decade. At its height its collection reflected the rich history of Afghanistan’s strategic position on the Silk Road between China and Europe. Soviet troops who invaded Kabul in 1979 treated the collection with respect but in 1992, three years after they left, rival Afghan Mujaheddin factions fought for control of the city. The museum repeatedly changed hands among different groups, who plundered as they went. By the time museum staff managed to get access to the building in late 1994, 90 percent of the collection had disappeared. Some of it had been destroyed, but most had been looted.

Since then friezes and statues, including some masterpieces of Buddhist art have appeared on the market. Some have been bought by public collections, such as Paris’ Musee Guimet; others have been bought by private collectors, especially in Japan. According to Robert Kluyver of the Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage, such individuals pay up to $1 million for a Buddhist schist [panel] from the Gandharan period, when Buddhist art was produced in Greek-influenced styles. Unsatisfactory as this may be, it is a strange irony that art lovers and Buddhists may have cause to be grateful that the corruption and rapacity of the Mujaheddin has saved at least some of Afghanistan’s Buddhist artfrom the Taliban.

Despite what the Taliban may think, Buddhists do not worship images themselves but what the images represent: the bamiyan Buddhas embodied the Wisdom and Compassion of the Buddha. Buddhists are likely to respond less with anger at the loss of the statues than sadness at the ignorance that motivated it. And theywill realise that the Taliban’s war-bred fanaticism does not even speak for the whole of Islam.

|

‘In the name of Allah, the Beneficient and Merciful, (The Koran, Surah 108 ) |