Contemplating the Navel

Bodh Gaya in northern India has been called 'the navel of the universe', the place where Buddhism started when the Buddha gained Enlightenment. A bodhi tree still stands in the grounds of the Mahabodhi temple that is believed to be a descendent of the original tree beneath which the Buddha sat in meditation. As Buddhism becomes a global religion, Bodh Gaya is becoming a focus for Buddhists from many traditions. Yet it is in Bihar, the poorest and most lawless state of India. Bodh Gaya demonstrates the paradoxes, challenges and conflicts that Buddhism faces in the 21st century.

In early 2001 inspectors from the United Nations visited Bodh Gaya to assess its suitability to become a World Heritage site. Every year thousands of people visit, the great majority of whom are Buddhist pilgrims who come to practice around the Mahabodhi Temple. The town is developing rapidly, new hotels and restaurants opening every year to cater for the increasing number of visitors. If Bodh Gaya becomes a World Heritage Site this development will almost certainly increase. As well as Buddhist pilgrims, it will attract much larger numbers of tourists.

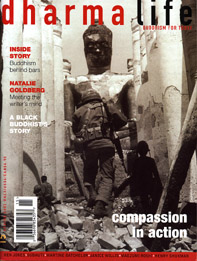

By far the largest development is the Maitreya Project of the Tibetan Buddhist organisation, the Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) that is now taking shape on 40 acres on the outskirts of the town. It will focus on a huge statue of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, which at 150 metres will be the largest statue in the world, three times the size of the Statue of Liberty. The base on which the Buddha sits will contain a complex of lavishly decorated temples and other facilities. When it was first announced in 1995 the cost was estimated at $5 million, but the FPMT's latest fundraising material puts the cost at $195 million.

Will this development benefit the people who live in and around Bodh Gaya? As the poorest and least developed Indian state, Bihar has the lowest literacy rate, highest number of deaths in police custody, worst roads, and highest crime in all of India. Its per capita income is less than half the Indian average. Villages around Bodh Gaya have been the scenes of vicious inter-caste violence while revolutionary communist militias are engaged in a low-level civil war with the private armies of local landowners. Estimates put the numbers killed in caste-related violence around 6,000 per year. In 1997 there were 2,625 murders, 1,116 kidnappings and 127 abductions.

Despite Bihar's poverty and its population of over 60 million, it recives little international aid because most development agencies consider that the level of state and local government corruption make it impossible to work there. Many members of the State legislature – and this includes the Chief Minister and several members of his cabinet – have been charged with crimes including rape and murder. According to journalist critics, they enter parliament through election rigging, and stay out of prison because their position affords them immunity from imprisonment on remand. The justice system is so chaotic that it will be many years before their cases come to court.

Many local people feel strongly that there should be a greater attempt to ensure that the development of Bodh Gaya as a pilgrimage and tourist site provides benefits to the local community. But attempts to alleviate poverty and deprivation tend to be small-scale initiatives funded by concerned individuals. However several schools in Bodh Gaya are run by Buddhist organisations, and other projects enable Buddhists visiting Bodh Gaya to make a contribution to the lives of local people.

In the Pachati district of Bodh Gaya an organisation called People First runs a small educational hostel for 27 boys from local villages who would otherwise not be able to complete their education. People First also runs a network of schools in 13 villages that cater to over 2,000 children – most of whom would otherwise have no schooling. Many of these villages have school buildings but no teaching takes place in them. In Bihar it is common for a teacher to draw a salary but never go to the village to teach, instead giving a bribe to the local government official to turn a blind eye.

People First has also recently started building a vocational training centre to provide training in skills that will enable children from the local villages to find work. The project is funded by donations from the Karuna Trust, a UK Buddhist Charity. They work with the organisers of one of the larger vipassana meditation retreats to provide an opportunity for retreatants to visit the villages and meet locals. The impact of such initiatives is tiny in relation to the scale of the Bihar’s problems, but they make a small contribution to alleviating the sense that tourists and Buddhist pilgrims in Bodh Gaya inhabit an island of affluence in an ocean of poverty.

This is precisely the danger faced by the Maitreya Project. For several years the FPMT’s Root Institute, a retreat centre catering for western visitors, has run a polio clinic. But this threatens to be dwarfed by the new development. There has been much criticism of the contrast between the expense of the Maitreya Project and the poverty of the region, and plans now include an international-standard hospital and (perhaps more relevant to regional needs), a primary health care dispensary that will serve thousands of people. There will also be a new school for 300 local children.

The FPMT insist that the main benefit of the statue will be the merit it brings those privileged to see it. Peter Kedge, the Project's Director comments (in a publicity CD) that ‘there is a unique, powerful quality in statues that the imbues the consciousness of those who encounter it’. While Tsenshab Rimpoche, expressing views that are traditional within Tibetan Buddhism, declares: ‘If we build such a big statue, all the troubles of the world will be pacified’.

No one has suggested that such claims are insincere nor that the statue does not express the sincere devotion and good intentions of those Tibetan Buddhists responsible for it. But the debate among Buddhists continues. Christopher Titmuss, a well-known meditation teacher who has run retreats in Bodh Gaya for many years, believes the statue will cause environmental damage, depleting the already dangerously low water level, while offering little material benefit to locals. He argues that the money saved by taking three metres off the height of the statue could provide education, vocational training and environmental programmes throughout the region. In a recent article he also suggests that there are ethical issues within the Tibetan community that need to be addressed: ‘During the 1990s, Indian contractors bought children ... for around 150 rupees ($4) and sold them to Tibetan merchants for child labour elsewhere in India (I have deeds of sale)’.

It seems certain that the Maitreya statue will be built, that Bodh Gaya will attract more and more visitors, and that these will include tourists as well as pilgrims. This is bound to bring tensions: hostels for western travellers already have armed guards, and the Maitreya Statue will need high security to protect it from Bihar’s bandits. It is easy to imagine Bodh Gaya as a focus for world Buddhism and a beacon for people around the world. But realising this vision will require commitment to the broadest possible sense of the transformation the region requires.