Jungle Bound

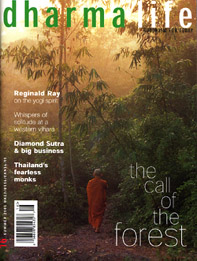

Entering imaginatively into the mind of the Indian poet-monk Shantideva, Padmakara contemplates the timeless appeal of forest life.

My first substantial encounter with Shantideva was in the mountains, cradled in a forest grove of holly oak and pine trees. These mountains were not jewel-formed but beautiful, rugged Spanish limestone. The boughs of the trees were full of pine-cones that cracked open in the sun. I was not in solitude but with a group of friends in Spain, on a retreat, studying the text from which this quote is taken. I have returned to this text many times for personal inspiration and to lead others through it in group study. Each time I read it I become more fascinated by the character of its author, Shantideva. There are few historical records yet in my mind some sense of his character has formed. Perhaps my picture is more impressionistic that realistic. Yet maybe that is the only way we can ever envisage figures on the fading canvas of history.

Shantideva (c.685-763 CE) wrote this verse as part of an elaborate, poetic and imaginative offering to the Buddhas. Over 1,000 years had passed since the Buddha's time and the tradition, it seems, was still alive in his monastery in what is now the Indian state of Bihar. Yet although the tradition was alive, it had changed. Buddhist practice had become increasingly associated with settled monasticism and scholastic elaborations of Buddhist teaching. In the Buddha's day, although basic dwellings or viharas were built for the Buddha and his disciples, the emphasis lay on wandering rather than settling down.

What was the relationship between the wandering lifestyle of the Buddha and the more settled lives of many later Buddhists? The question addresses certain tensions that are pertinent to our understanding of the Buddhist tradition and to our own practice as Buddhists. When do we need supportive institutions and when could we leave them behind? When do we need to study with others and when simply to meditate alone? When do we need the 'monastery' and when the 'forest'? – both literally and metaphorically. Shantideva seems to be aware of these issues and sheds some light on them for us.

Shantideva was a scholar-monk who left a princely background to study at Nalanda, the famous monastery-cum-university that flourished between the fifth and twelfth centuries ce in northern India. Around the monastery and on the surrounding hills stretched miles of forest and woodland. Natural beauty and wildness would never have been far from the minds of the monks, even amid the walls of the institution. It is not surprising that Shantideva considered the solitude of forest groves a worthy offering to the Enlightened ones.

From the legend we know that Shantideva didn't seem to fit in with Nalanda's routines and curricula. Fellow students nicknamed him 'Lazy-Bum', and his only attainments were said to be 'eating, sleeping and defecating'. One day he was challenged to give an original and extensive teaching to the gathered monks. Rising to this challenge, he delivered the poem now known as the Bodhicaryavatara, levitated into the air and disappeared, only his voice remaining to conclude the teaching. Then Shantideva left Nalanda, never to return.

We don't know what happened to him after this, though one legend has it that he became one of the 64 mahasiddhas or forest tantric practitioners. In the absence of historical evidence I like to think of Shantideva following this legendary path from prince to monk to forest wanderer. There is a mythic satisfaction in that journey that has its own validity.

In looking for evidence to support my fantasy we must turn to the text of the Bodhicaryavatara. The title means 'the Training on the Way to Awakening'. It is a manual for aspiring Bodhisattvas in which Shantideva cajoles and challenges; and he offers his fellow disciple with an assortment of sticks and carrots. The structure is an initial 'Praise of the Awakening Mind (bodhicitta)', followed by a section on 'Supreme Worship' (anuttarapuja) and then the Six Perfections of the Bodhisattva path spanning generosity (dana) and ethical conduct (sila) through to forbearance (ksanti), vigour (virya), meditation (samadhi) and ultimately wisdom (prajna).

The whole text takes us on a systematic, profound and yet ultimately mysterious journey. What makes it so engaging is Shantideva's obvious sincerity and enthusiasm for what he is propounding. The Bodhicaryavatara is no dry technical treatise but a testament to a passionate practitioner, written in a high literary style appreciated across the centuries. The text is the product and pinnacle of Shantideva's monastic experience. It justified his training at Nalanda. But where does one go from a pinnacle? Perhaps over the walls and into the forest?

It seems that Shantideva was well aware of the forest as a place of potential solitude and deep meditation. In his Siksa Samuccaya – a compilation of writings from the sutras that Shantideva is thought to have put together before he wrote the Bodhicaryavatara – a whole chapter is devoted to 'Praise of the Forest Seclusion':

'There never was a Buddha aforetime, nor shall be in future, nor is there now, who could attain that highest wisdom whilst he remained in the household life. Renouncing kingship like a snot of phlegm, one should live in the woodland in love with solitude; renouncing passions, rejecting pride, they awaken wisdom unsoiled, incomposite ...'

And yet he is drawn to another quote from the Ugradatta-pariprecha:

'To what end do I live in the forest? Not only by the forest life does one become an ascetic. Many live there who are untamed, uncontrolled, not devoted, not diligent ... when the Bodhisattva has left the world and settled in the forest, if he feel fear or terror, this is how he must school himself: 'Whatever fears may arise, they all arise from self-seeking ... But if when dwelling in the forest I should not renounce all clinging to self, nor belief in self, the notion of self ... useless would be my forest life'.'

So the forest is not simply a refuge in itself, it is a context of practice and in particular the practice of transforming the self-cherishing attitude. Without this attitude the forest life is 'useless'; the forest life is a means and a method, not an end in itself. When he writes about the forest, Shantideva seems to communicate a longing. I imagine him sitting studying alone in a small cell, or perhaps wandering around Nalanda among the hustle and bustle of monastery life; he is reflecting on some pithy Dharma problem, perhaps on how he can best practise amid some of the monks who have been mocking him or accusing him of laziness. Then I see him stop, perhaps lingering at the entrance gate. I see in his mind's eye a vision of a peaceful glade, shaded from the hot sun. He reflects: 'Trees do not bear grudges nor is any effort required to please them. When might I dwell with those who dwell together happily?'

Staying in an empty shrine, at the foot of a tree, or in caves, when shall I go, free from concern, without looking back?

When shall I dwell in vast regions owned by none, in their natural state, taking my rest or wandering as I please?

When shall I live free from fear, without protecting my body, a clay bowl my only luxury, in a robe that thieves would not use?

(Bodhicaryavatara, ch.8, vs. 26-29)

It seems that here he is expressing a deep longing to let go, to go forth, perhaps not only from the monastery but from all attachment. Perhaps we can find a resonance here? Do we not also feel a longing for simplicity in our complicated lives? Even in friendly and supportive surroundings do we nevertheless feel a need to go further? With loved ones do we not feel some sense of entanglement that limits our being? Do we not feel that sometimes, despite all its wonderful practicality and compact functionality, we would be freer without our beloved computer? For most, if not all of us, the idea of literally retreating into the forest is simply not an option.

Aside from the sad environmental fact of ever-shrinking forestland, social and religious conditions are simply unsupportive of such radical moves. In the light of this perhaps we can consider the metaphorical value of the 'forest'. In this way the 'forest' becomes any space in which we can create the conditions for distraction-free meditation. A period of meditation in itself can be a journey to the grove. A retreat in the countryside, alone or with others, can give us the break from everyday habits and familiarity. The point is to lessen our worldly attachments so that we can liberate a more altruistic attitude towards the world.

Shantideva states:

'Thus one should recoil from sensual desires and cultivate delight in solitude, in tranquil woodlands empty of contention and strife.

On delightful rock surfaces cooled by the sandal balm of the moon's rays, stretching wide as palaces, the fortunate pace, fanned by the silent, gentle forest breezes, as they contemplate for the well-being of others.

Passing what time one pleases anywhere, in an empty dwelling, at the foot of a tree, or in caves, free from the exhaustion of safeguarding a household, one lives as one pleases, free from care.'

(Bodhicaryavatara, ch.8, vs.85-87)

This, in contrast to the struggles of the Wheel of Life, releases within us a sense of potential liberation and spacious freedom. Shantideva's poetry seems wonderfully able to spark a longing for meditative solitude. So Shantideva is saying that we do need, at least to some degree, a retreat from the world. Yet at the same time the image of the forest grove stands in contrast to the city life as Nirvana to Samsara.

Up until now Shantideva has been hacking a path through the forest, resolutely working his way through difficult terrain. At this point in the text he reaches a clearing, his jungle destination, free of dust, disputes and distractions. Here the 'fangs of the defilements' have relaxed, here is a turning point. And it is literally a turning point for it is now that, having fought his way from the turmoil of the world, he stops in the stillness and turns round to face it all. The forest grove is not an end. It is the base and beginning of compassion. It is the place where the heart is free enough and large enough to embrace the sufferings of the world.

'By developing the virtues of solitude in such forms as these, distracted thoughts being calmed, one should now develop the Awakening mind.'

(Bodhicaryavatara, ch.8, vs. 89)

By chance I recently came across some quotes from the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, a man who was also deeply concerned with both the necessity of solitude and the suffering of beings. The setting is apt:

'I am spending the afternoon reading Shantideva in the woods near [my] hermitage – the oak grove to the south-west – a cool, breezy spot on a hot afternoon ... What impresses me most – reading Shantideva – is not only the emphasis on solitude but [his] idea of solitude as part of the clarification [necessary for] living for others: [the] dissolution of the self in 'belonging to everyone' and regarding everyone's suffering as one's own. This is really incomprehensible unless one shares something of the deep, existential Buddhist concept of suffering as bound up with the arbitrary formation of an illusory ego-self. To be 'homeless' is to abandon one's attachment to a particular ego – and yet to care for one's own life (in the highest sense) in the service of others.'

(T. Merton 'The End of the Journey' Journals, vol. 8, p. 135)

The forest, then, becomes a symbol of paradox. In remoteness, care arises. At a distance human engagement is stimulated. But, as Merton understands, the paradox is resolved when we realise the problem is the self-grasping ego. The forest is not just a place of calm detachment but an intense mirror on our limited – ultimately false – sense of self.

Once in the forest grove Shantideva suggests a profound two-stage meditation or insight reflection. Firstly we are asked to meditate on the equality of ourself and others, in the sense that all equally have the experience of suffering and happiness. This equality is the defining fact of the human condition and thus we should care for others as we do ourselves. Secondly he goes a step, a radical step, further. We are asked actually to exchange ourself with others. In other words we have to make the imaginative leap that others are more important that ourself. In this radical self-transcendence we are able to abandon our identity with our habitual self-centredness and to re-identify with the universality of life as a whole.

The turning point is complete. Perhaps we will never know what really happened. Scholars will no doubt be unhappy, but I stick to my, not implausible, story: Shantideva went from the books and backbiting of the monastery into the forest. He hacked a path of perfection to the deep glade of meditation. He sat and reflected on his sufferings and the sufferings of the world and then, who knows, perhaps he lifted into the air again, as he did during his recitation of the teaching of the Bodhicaryavatara. Or perhaps, if he attained what he sets out in his teachings – like the Buddha returning from the Bodhi tree – he would then have arisen from the forest grove, walked steadily back along the forest track and re-emerged into the needy world.

Although my reflections are inconclusive, I am still left with something fairly clear: spiritual life is a journey towards wholeness. Whether one is a prince or a pauper, a mother or nun, a family man or monk, a scholar or forest renunciate, there is always another step to take. The path does not end at any of these places. From each place wisdom is to be won. Even if we reach the forest grove, in whatever form that takes, we still have to make the return journey. In the forest grove we may discover gold or grace or maybe just a handful of green leaves. Either way we need to offer what we have won back to the world with its endless sufferings.