Brothers in Alms

Based on shared values of compassion and truth, the bond between Matthew Webb and Tejadhamma transcends continents and contrasting lifestyles

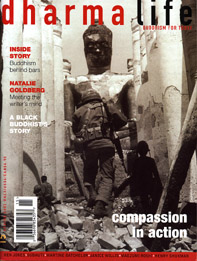

Two friends stand on a rooftop in Nagpur, home of the rebirth of Buddhism in India. Just a few miles away, in 1956, Dr BR Ambedkar led 500,000 of fellow so-called ‘untouchables’ out of the prison of the Hindu caste system and onto the path to freedom that is the Buddha’s teaching. Both of us were born more than 15 years after Ambedkar’s defiant act but the direction of each of our lives has been greatly influenced by it.

We are both Buddhists and work in different ways for the uplift of Ambedkar’s ‘untouchables’ (now known as Dalits). One is Tejadhamma, a member of Trailoka Bauddha Mahasangha (the Western Buddhist Order in India) who is responsible for three educational hostels around Nagpur that are helping 116 children to get an education. The other man is me, a door-to-door fundraiser for the Karuna Trust, which finances those same hostels, along with similar projects around India.

How did we come to be standing together on this baking-hot rooftop, initiating a friendship that I hope will last the rest of my life? I was born into a world of privilege and material plenty, Tejadhamma into Indian slums. It was as though we had been born into different realms: one apparently heavenly, one apparently hellish. The eldest of six children, he suffered the hardships of birth into Ambedkar’s own sub-caste, the Mahars. I enjoyed pleasant diversion in my foam-padded childhood: ski trips and Disney World, boarding school and Cambridge. I washed silver Audis and delivered the Daily Telegraph to afford a BMX bicycle or a colour TV. Tejadhamma dug roads and fields for four hours either side of his school day so that his family could live. The only expectation thrust on me was that I should work hard and succeed. Tejadhamma had to finance his sister’s wedding (a local loan shark was happy to oblige). Tragedy for me was failing my driving test. Tragedy for Tejadhamma came when that same sister was burned to death by her new husband and mother-in-law because the dowry was insufficient.

As a young man I strode determinedly out from my suburban childhood into the spiritual desert of 1990s Britain, my mind set on accumulation rather than reflection. I was at liberty to drink inspiration from the oases of art, music or religion. Yet I paid scant attention to these. I was not thirsty so why should I stop? I travelled on briskly, blessed with good health and abundant energy, towards whatever hazy vision occupied the horizon. The vision varied – sometimes a prestigious City job, a GB triathlon vest, or a glamorous woman – but all the while I was driven by a largely unconscious sense that on reaching the vision I would finally experience peace, contentment, and liberation from the need to strive further. But each vision proved, of course, to be a mirage.

The only pursuit that left any trace, and proffered hope of security and liberation, was making money. By talking into a telephone for 12 hours a day, buying and selling other peoples’ money, a tiny but significant percentage would appear in my bank account every month. It seemed too incredible, magical even, but these numbers were no mirage. They really existed, no one could take them away, and they didn’t slowly evaporate like happy memories. In fact they grew the longer you left them alone! What’s more, they could be converted at any time into all sorts of pleasures – holidays to China, tailor-made suits, Conran lunches. But after three years even this magic faded. I was waking at 6am, working myself into an anxious, irritable frenzy all day and then trying to attain the body beautiful in the gym or pool each night. Where was the peace, the end of striving?

‘Just a few more years of this,’ they told me (the management consultants, investment bankers, corporate lawyers), ‘then you can retire and enjoy ease’. But I was impatient – I’d had enough. I’d given materialism its chance and it just wasn’t delivering. But what other options did the working world offer? At about that time I attended a talk at the London Buddhist Centre aimed at recruiting volunteers for Karuna’s door-to-door fundraising appeals. I was not attracted to the idea but suspected that I would do well, having been a successful door-to-door salesman years earlier; and I saw it as a chance finally to give something to the world.

Soon after the appeal began I knew I had stumbled across a very effective spiritual practice – I was benefitting at least as much from door-knocking as the beneficiaries in India. In the subsequent 18 months I have worked on five such appeals, exchanging the glory of the $100 million bond deal for the satisfaction of a £20-a-month covenant; dreams of a Porsche Boxster for the reality of the No. 73 bus, the City of London for the lonely avenues of Cardiff, Sheffield or Brighton – or wherever the next appeal happens to be. I knock on peoples’ doors and ask for money. Pounds that buy Rupees that help Tejadhamma to transform lives. Some people say yes, most say no; but everyone gives me something, if only an appreciation that a world exists beyond myself (something I have only recently begun to suspect).

The young Tejadhamma also dreamt of liberty, but for him this was accompanied by the equality and fraternity of Dr Ambedkar’s vision of a new society, free of the cruel strictures of the Hindu caste system. Tejadhamma initially tried to bring this vision to life through practising and teaching karate with friends from the SSD (Soldiers of Equality), an Ambedkarite organisation founded in 1927. This militant-sounding combination proved to be an excellent way of bringing together children from different, often antagonistic, communities and give them the gift of self-discipline and respect for themselves and others. With nothing more than their share of the dusty local wasteland, Tejadhamma and friends taught karate for three or four hours, six days a week. They learnt the art from books because they had no teacher and wore white belts instead of black because they had no money for gradings.

In 1988 some friends of Tejadhamma attended a lecture by Sangharakshita, founder of the WBO/TBM. They were so inspired by Sangharakshita’s exposition of the Dharma (previously an attractive but mysterious collection of spiritual teachings) that they soon left the SSD and devoted themselves instead to the work of TBM and its social-work wing Bahujan Hitay. Tejadhamma joined them and over the subsequent decade this heroic gang of five or so men gave the inspiration and energy to a spectrum of social projects in Nagpur that have transformed thousands of lives: slum kindergartens, educational hostels, adult literacy classes, music and drama courses and, yes, karate classes.

Recently Tejadhamma and his friends realised their grandest vision so far – Nagaloka. In this 15-acre complex stands a glorious shrine building, an open air meditation hall, Dharma library and teaching facilities (the Nagarjuna Institute), residential community for men and offices for Bahujan Hitay offices – all perfumed by row upon row of roses and nishigandha (‘night fragrance’) flowers.

Last November Tejadhamma and I finally met. I immediately warmed to his friendliness, his ready smile, his generosity and his patience. But most of all I was struck by how much, despite appearances, we have in common. Each of us tries to express the altruistic ideal in different ways, on different continents, in different cultures, with different lifestyles (he provides for a wife, young son and ageing parents, while I provide for just myself). Yet we each find our inspiration in the same great river of compassion that has flowed to us from the Buddha.