Dreaming Me

Jannis Wilis, Professor of Religion at Wesleyan University, is the first prominent African-American scholar of Tibetan Buddhism Named by Time Magazine as one of six religious innovators for the new millennium, she is motivated by experiences of racial inequality and the transforming power of meditation. She spoke to Suryagupta about her new autobiography.

Dreaming Me is framed by a series of dreams about lionesses which occurred while she was tracing her family history. ‘The lions invaded my dreams and my pysche ...The lions are me. Perhaps they are my deepest African self. They are the “me” that I have battled with ever since venturing forth into a mostly white world. I believe it is time to let the lions come to the fore and to make peace with them. For making peace with them is making peace with myself, allowing me to be me, authentically.’

To meet Willis is to see this lioness’ quality embodied. We first met eight years ago and discovered a strong connection. I was impressed that as well as being deeply imbued in the study and practice of Tibetan Buddhism, Willis also teaches black studies. She was only the second other committed Buddhist woman of African descent I had met, and we also shared a connection with the Tibetan teacher, Lama Yeshe. Recently I hosted a reading from her memoirs and I was again struck by her manner, which reflects this mix. She is very expressive, down-to-earth, but with a sense of something imaginative and mysterious, and she speaks freely of meditation, dreams and visions. I related to the way she talked about Buddhism; for her part she said she had never been among so many black Buddhists as attended her talk (who came via the London Buddhist Centre where I have taught courses aimed specifically at black people).

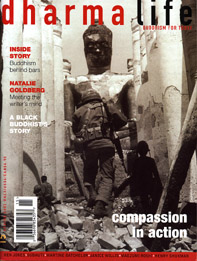

Dreaming Me depicts Willis’ childhood in a southern Baptist town, her active involvement with the civil rights movement, her travels to India and her relationship with Lama Yeshe. Coming to terms with her true self involved making peace with her turbulent past growing up in the South.

Growing up in Alabama

‘“Don’t go too far”, my mother always reminded me as she pushed open the screen doors and I rocketed forth, straight past her.’ In Alabama these words were more than ordinary motherly advice. They contained a warning: Don’t cross the line, the rigid racial boundaries that ran through the mining village of Docena, Alabama. For a black child growing up in the racially segregated South, the consequences of not adhering to the geographical and social limits were severe. ‘Every so often Docena’s Klan reminded us blacks of our ‘proper’ place. Their tactics were simple: they reminded us who was boss by instilling in us fear of the consequences of ever forgetting it. None of the blacks who lived in Docena were spared the Klan’s reminders. On a fairly regular basis, there were drive-throughs and cross-burnings in the camp.’

Even a trip out in the family car warranted the warning not to wind down the window for fear of Ku Klux Klan members throwing acid at them. The threat of violence at the hands of the Klan was ever present for Willis and her family. On one occasion she woke to find Klansmen, women and children – her neighbours – burning a cross on her front lawn. ‘The minutes stretched into eternity as we waited for a bomb. But, cross ablaze and garbled speeches delivered, the Klansmen and women and their enrobed children got back into their cars and rode away. For whatever reason that night our lives were spared.’

The psychological effect of such experiences was crushing, and it would take years of Buddhist meditation under the skilful guidance of Lama Thubten Yeshe before Willis could directly engage with a process of transformation and healing. Yet, somehow, despite the oppressive conditions she was able to see and think beyond the limitations imposed by segregation. Her keen intellect was noted by family and teachers, and this brought both encouragement and trepidation since no-one in Docena dared to dream big dreams for a black girl, for whom the world might prove an unkind place. But Willis was compelled to go beyond her mother’s advice not to venture too far, and she was one of only four pupils in her year to go to college and the only one to attend one of the prestigious Ivy League universities in the North.

Fortunately there was more to life in Docena than the Klan, as the small mining village contained a source of religious inspiration. Although Willis had to be cajoled into being baptised, that baptism became her first spiritual experience. ‘It was as though my family became infinitely larger. I had joined a new community and there was strength and grace there.’

Willis now embraces her Baptist roots by calling herself an African American Baptist Buddhist, and she sees no contradiction. ‘It’s the most honest description I can give of myself,’ she says. ‘When I’m working through some important issue, I turn to Buddhist principles, but when times are really dire I call on both.’ In Dreaming Me Willis recounts the story of a plane journey to illustrate the point. ‘The plane veered steeply upwards ... We were like astronauts, our heads pressed back against our seats, our bodies feeling the G-forces of lift-off. My knuckles went white. Papers from somewhere started blowing through the compartment. Overhead doors snapped open. Oxygen masks dropped. Some people started to scream. I started to pray, at first aloud and then silently, but speeded up with urgency. I screamed, “Lama Yeshe, may I never be separated from you, in this and future lives!” Gripping my arm rests, in silence, I continued, “May you and all the Buddhas help and bless us, now!” Without pausing, I then fervently intoned, “Christ Jesus, please help us. Please, I pray, bless me and all these people!”’ She quotes Kirkegaard’s dictum: ‘One doesn’t know what one really believes until one is forced to act.’

Black Panthers or the monastery?

In the late sixties the United States was in the grip of social and political upheaval. The Vietnam war was stirring young and thoughtful Americans to protest; Martin Luther King, who had led the peaceful movement for social justice, had been assassinated. The new word on many lips was ‘revolution’. Black radicals felt the need for a more assertive strategy to fight injustice feeling that, despite years of peaceful demonstrations and sacrifice on the part of black activists, nothing fundamental had changed. The Black Panthers emerged, taking ‘a more aggressive stance’ and prepared to use violence if necessary. Equal rights had still to be achieved. This meant they would no longer try to raise the conscience of America by enduring the violent opposition to peaceful demands for justice, but would advocate ‘self defence’. For the first time the fight for equal rights took on a military stance.

This threw Willis into turmoil. Like many of her contemporaries she had already discovered Buddhism through the works of Alan Watts and DT Suzuki. The images of Vietnamese monks and nuns protesting against the war and persecution of their religion by setting fire to themselves while meditating and chanting had impressed her deeply. Transformation through non-violent means strongly appealed, yet her experience had not proved that the way of peace worked. Even though she was now at the elite Cornell University she still felt the impact of racism. She found good friends, but she felt the hostility and hypocrisy of their parents. One night a cross was burnt on the lawn outside a black women’s residence.

Willis first went to India in her junior year at Cornell, studying Buddhist philosophy at a summer school. While visiting a Buddhist festival she met a monk who told her she should study at the monastery and she corresponded with the monk even after her return to Cornell. In her senior year one of her professors asked her what she planned to do after graduation. A choice presented itself: armed struggle and revolution with people she knew and respected in the Black Panthers, or the way of peace in the Tibetan monastery. She hadn’t thought through the implications of violence but, she told me, ‘I saw that non-violence hadn’t worked and thought there must be another way. In the end I felt too afraid and too confused to take up guns. Besides I’d always preferred peace and non-violent methods’. Willis’ professors made her a unique offer: she would be admitted to graduate studies at Cornell and granted her first year there in absentia, which meant she could return to the monastery at Cornell’s expense. ‘When I finally decided to study at the monastery a huge weight fell from my shoulders.’

Joy of the Dharma

When she first met Lama Yeshe Willis was impressed by his smile, his gentleness, and his intelligence and quickness of mind. ‘He understood me in ways I didn’t understand myself.’ Studying Tibetan Buddhism with more than 6o monks and engaging in visualisation practices, Willis discovered the tools she needed to free herself from confusion and anger. Meeting Lama Yeshe and the community of Tibetan exiles provided her with essential support. ‘Tibetans are a wonderfully joyous and gentle people who have managed to cope with a historical trauma in some ways similar to black folks’. They took me in right away and for that I’m grateful.’ Some time later she discovered her vocation teaching Buddhism at University level and translating Tibetan texts.

Willis emphasises that her transformation is still under way and the journey to freedom is by no means complete. However, she has found a continual source of inspiration and peace through the Dharma and Lama Yeshe.

When she first encountered Buddhism Willis was outwardly strong and confident – a high achiever. But she now thinks that this proud exterior masked ‘a lifetime’s worth of self-pity and low self-esteem’. It took her 10 years of Buddhist practice before she could confront the racial dimension of this insecurity and put aside her anger. Of her first meeting with Lama Yeshe she says: ‘It was as if he was saying “Let the old wounds go, daughter. Let them go.” Standing there with him, for the first time in my life I began to feel that I could let them go. Let them all go and embrace my true self, which was like the true selves of all other beings, clear, confident, capable, loving and loveable. At that moment confidence arose within me and I knew that everyone ought to feel this way.’

Tibetan tantric practices, such as reflecting on one’s essential inner purity, or visualising oneself a Buddha, were also helpful. In time Willis saw the inner causes of her discontent, as well as the outer, social causes. ‘Whenever our suffering takes the guise of self-pity or self-absorption, the source is always the same: holding too tightly onto our projected image of ourselves. We know, for example, that when we are depressed, our minds turn around one point: me. Poor me. Why me? How could this have happened to me? The nub is always me, me, me ...’

Through her years of practice Willis has come to embody the Dharma name given to her in 1969 by Geshe Rabten, Lama Yeshe’s teacher, which translates as ‘Joy of the Dharma’. She is now well known for the passion, clarity and humour with which she communicates both the letter and spirit of Buddhism.

Healing the divide

There have been three decades of equal rights for African Americans and affirmative action programmes have attempted to redress the social and political imbalances caused by the history of slavery and racism. Yet when I asked if racism still has a strong effect on American society, Willis did not hesitate. ‘Absolutely and unquestionably. An excellent example was the recent travesty with our presidential elections and the disqualified or uncounted votes in Florida.’ The majority of these votes were cast by black people, which brought questions for people who had fought for civil rights over many years and believed they had been successful.

According to Willis, ‘mainstream Buddhist groups consist of mainly white “elite” Buddhists, and that reflects the divide in society’. In fact there are very few African-American Buddhists and mainstream Buddhist groups are often not successful in maintaining the interest and commitment of blacks. Willis argues that both blacks and whites come to Buddhist practice with a great deal of racial conditioning. Whites have imbibed often negative messages and views about blacks and their position in society from history books, popular culture, and from family and friends. Blacks’ memories of the struggle for legal and political rights and the history of racial subjugation means that they enter a mainly white context, such as a Dharma centre, with trepidation. So even in the calm and positive environment of a Buddhist centre racial history and experiences of racism will be present. ‘I don’t think there is any reason to think that our Sanghas are so different from the larger societies in which we live. Prejudice exists there as it does in society, even if there is an attempt to do better,’ says Willis.

Willis would like to see more cultural and ethnic diversity within Buddhist groups, so she is raising awareness of racial issues in Buddhist communities. She sees this as a way for both black and white Buddhists to free themselves from negative conditioning. Her approach is to address the issues using tools with which Buddhists are familiar. ‘I think we need to use what we know how to do best, namely meditation.’

Meditative awareness can be brought to the subject of race:‘We need to develop contemplative exercises geared to developing awareness of race and transforming negative judgements into positive ones.’ Willis uses the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism’s technique of contemplating teachings and ideas, and she introduces these into workshops on race.These workshops explore how we relate to difference, and introduce Buddhist values and principles, such as loving-kindness. She cautions, however, that before engaging in these activities it is important to have a ‘safe space’ where there is a degree of trust and openness: ‘The subject of race raises a lot of intense and difficult emotions’. Whites tend to feel guilty or defensive when the subject is brought up, while blacks often resent having to educate others about their experience and history. She is confident , though, that addressing the issue directly can bring deeper harmony and understanding.

Willis draws inspiration from her first meeting with the Dalai Lama during a student protest at the height of America’s civil unrest. He advocated patience, clarity and loving-kindness when faced with difficult situations. For Willis these are the same qualities needed to explore differences based on race or culture. ‘We need the imaginative exchange of self and other ... placing oneself in another person’s shoes and recognising the preciousness of another human being.’ For Willis this is the meaning of the title ‘religious innovator’ she was given by Time magazine. ‘I think teaching and raising awareness about the racial divide and trying to fashion mediations to help transform negative judgements about others and oneself is worth doing. I’m trying to contribute what I can to that endeavour.’

Dreaming Me is published by Riverhead Books